Building Sovereign Data Lineage: A Decentralized Storage Architecture with DID and Proxy Re-Encryption

Preface

Traditional data governance presents an unavoidable contradiction: To use data, we must entrust it to a platform. Once entrusted, control no longer belongs to the Knowledge Contributor (hereafter referred to as Owner).

No matter how finely tuned a platform’s ACL (Access Control List) is, once data is downloaded, copied, or redistributed, access boundaries become meaningless. Single points of failure, internal privilege escalation, and unauditable authorization are not questions of platform discipline—they are structural outcomes of the centralized trust model itself.

This article addresses a more engineering-oriented question:

Can we enable data circulation without relying on platform trust, while ensuring control never leaves the Knowledge Contributor?

We adopted a hybrid architecture:

DID / VC (Verifiable Credential) + Data Version Control + Proxy Re-Encryption (PRE).

This architecture does not attempt to create a fully decentralized system. Instead, it uses cryptography to compress the platform’s role into a minimal, verifiable, and constrained function.

Core Design Philosophy: From Platform Trust to Cryptographic Constraints

This design follows four engineering principles rather than building another centralized data platform:

1. Minimal On-Chain Data

Blockchain’s value lies in immutability, not storage. The chain handles only data lineage attestation and state anchoring:

- No raw data on-chain

- No plaintext keys on-chain

- No full permission lists required on-chain

Only Contribution Fingerprint (CF), version relationships, and identity declarations remain on-chain; everything else stays off-chain.

Contribution Fingerprint: A receipt with provenance proof for a unit of work. When someone submits samples, labels, or validations (atomic contributions), the system creates a CF.

2. Data Sovereignty

Data sovereignty is not about who calls the shots—it’s about who holds the keys. The platform cannot access plaintext data or decryption keys at any stage without authorization.

This is critical:

- We do not rely on the platform being trustworthy. We enforce mathematical constraints that render the platform incapable of malice, regardless of intent.

3. Embedded Permission

Permissions are not database records—they are cryptographic facts embedded in the data structure itself. Permission is bound to data versions via VC. If you have:

- A valid VC

- The correct key derivation path

Then permission holds. Otherwise, it does not.

4. Auditability First

Every version evolution, authorization issuance, and revocation leaves a verifiable trace. Not everything goes on-chain, but any critical state can be verified by a third party.

System Architecture Overview

To balance decentralization ideals with engineering reality, we use a layered architecture that decouples storage, computation, and permission logic.

On-Chain Data Lineage Layer

This layer acts as a Data Provenance Registry. It stores no data—only metadata.

struct LineageRecord {

contributionFingerprint: Hash, // Hash fingerprint of data content

version: string, // Version number (v1, v2...)

previousHash: Hash, // Points to previous version, forming DAG or chain

operatorDID: string, // Operator's Decentralized Identity

dataUri: string // Off-chain storage address (e.g., ipfs://...)

}

Hash chains or DAG structures ensure data history traceability. Any tampering with historical versions is immediately exposed.

Off-Chain Storage Layer

This layer stores strongly encrypted data.

- Filecoin, Arweave

- S3 or similar object storage

- Or hybrid storage

We adopt a radical but practical assumption:

The storage layer is publicly readable by default. Data security relies entirely on encryption and key distribution.

Key & Permission Layer

The most critical and complex layer:

- VC answers: who can access which version

- PRE answers: how to deliver keys securely to the right person

Access Layer

The platform operates here. It:

- Verifies VCs

- Executes re-encryption

- Returns results

But it never gains decryption capability.

Data Evolution and Version Control

In production, data is not write-once-read-forever. We distinguish two concepts:

- DataEntityID: Identifies a dataset under a business context. Regardless of modifications, this ID remains constant.

- DataVersion: A snapshot at a specific time. This is the minimal unit for permission control.

DataEntityID (Business Object)

├── Version v1

│ └── ContributionFingerprint = H(data_v1)

├── Version v2

│ └── ContributionFingerprint = H(data_v2)

└── Version v3

└── ContributionFingerprint = H(data_v3)

Authorization targets versions, not entities. Accessing v1 does not grant automatic access to v2.

Let’s trace how this works using Codatta’s Food Science dataset as an example.

v1: Raw Collection

Data Content

You upload 10,000 high-resolution food photos covering packaged/unpackaged items and cuisines from various countries. This stage includes only images, basic GPS data, and metadata.

On-Chain State

- Version: v1

- ContributionFingerprint: SHA256(data_v1)

- previousHash: Zero_Hash

- operatorDID: Owner_DID

Permission State

Users with v1 access can download the raw images—data cleaning companies or teams doing visual model pre-training.

At this stage, data value lies in scale and diversity, not professional depth.

v2: Expert Annotation

Evolution Motivation

As model training progresses, raw images prove insufficient for nutrition recognition. You invite 50 nutrition experts to systematically label v1 data.

Data Changes

Structured annotations added:

- Calorie estimates

- Ingredient bounding boxes and labels

- Common allergen markers

On-Chain State

- Version: v2

- ContributionFingerprint: SHA256(data_v2)

- PreviousHash: Points to v1 (ensuring lineage continuity)

- operatorDID: Owner_DID

Key Strategy

v2 uses a new symmetric key $K_{v2}$, completely isolated from v1.

Permission Impact

- Users who purchased only v1 cannot access v2 automatically

- v2 can be separately authorized to commercial users—diet apps, nutrition analysis platforms

This step upgrades data from raw material to production-ready professional assets.

v3: Correction & Compliance

Evolution Motivation

During usage, you receive two types of feedback:

- Some nutrition labels contain deviations

- Some photos accidentally captured pedestrian faces, violating privacy requirements

Data Processing

You apply two corrections to v2:

- Fix incorrect or inconsistent nutrition labels

- Apply face blurring to privacy-sensitive images

On-Chain State

- Version: v3

- ContributionFingerprint: SHA256(data_v3)

- PreviousHash: Points to v2

- operatorDID: Owner_DID

Forward Secrecy & Permission Convergence

v3 uses a new key $K_{v3}$. You can re-authorize previous partners, but exclude companies that abused data.

Result:

- Excluded companies can still decrypt v2 data they legally obtained (irrecoverable)

- They can never decrypt v3 or any subsequent versions

In this v1→v3 evolution:

- Clear lineage: On-chain records trace the complete evolution path; any version’s origin is independently verifiable

- Granular authorization: Different versions target different markets—v1 for general visual tasks, v2 for consumer apps, v3 for medical/compliance-sensitive scenarios

- Sovereignty retained: Every version commit is signed by your DID. The platform is an execution/distribution node, not the data controller

Core Mechanism: Secure Key Delivery via Proxy Re-Encryption (PRE)

This is the highest engineering complexity in the scheme: how to distribute data keys without sharing the Knowledge Contributor’s private key or re-encrypting data for each user.

Key Management Strategy

Hybrid encryption:

-

Data encryption: Symmetric algorithms (e.g., AES-256). Each version $v_N$ generates an independent symmetric key $K_N$.

Symmetric encryption handles large data efficiently; asymmetric encryption performance degrades exponentially with file size.

-

Key protection: $K_N$ never leaves the Knowledge Contributor’s local environment in plaintext.

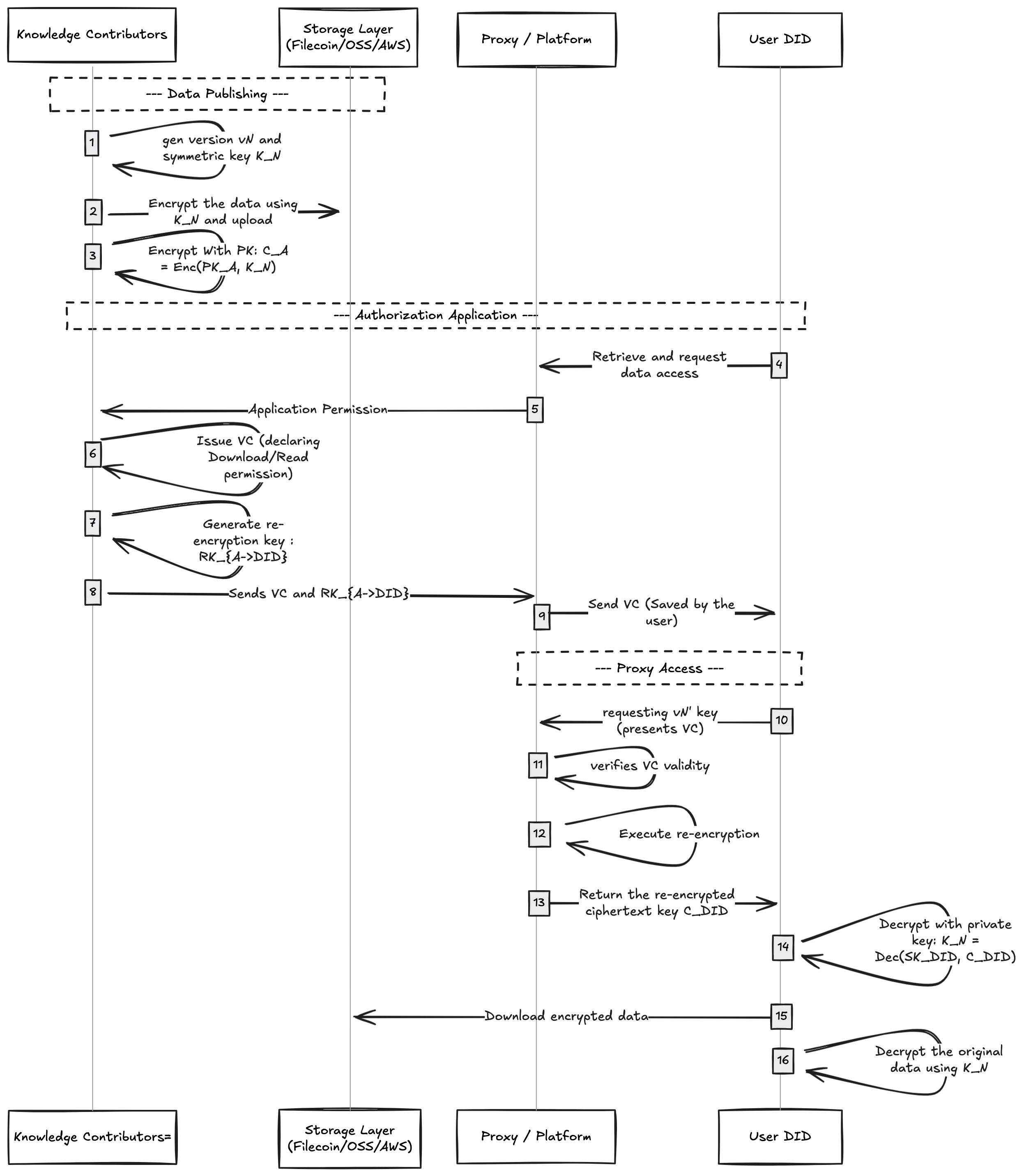

Full Authorization & Access Flow

The following describes the complete lifecycle from data publishing to user decryption:

Phase 1: Data Publishing

This phase establishes data sovereignty boundaries. Data is encrypted and version-locked before any system touches it. The platform sees only unreadable ciphertext. From this point, data exists not as a file, but as an encrypted asset fully controlled by the Knowledge Contributor.

- Generate key: Owner generates version $v_N$ and symmetric key $K_N$ locally.

- Encrypt data: Encrypt raw data with $K_N$ locally; upload ciphertext to IPFS/OSS/AWS.

- Self-encapsulate key: Owner encrypts $K_N$ with their public key $PK_A$, producing $C_A = Enc(PK_A, K_N)$, stored in metadata.

- Note: Only Owner can decrypt $C_A$.

Phase 2: Decentralized Authorization (via VC)

This phase answers: who can access which version? Authorization no longer depends on platform accounts or database records. VCs express permission ownership explicitly, making access rights a portable, verifiable, revocable fact—not internal platform state.

- Request access: User (User DID) requests access from Owner.

- Issue credential: Owner mints a VC declaring User DID has Download/Read permission for $v_N$.

- Generate re-encryption key: Owner generates a proxy re-encryption key $RK_{A \to DID}$ locally using the PRE algorithm.

- Technical principle: $RK_{A \to DID}$ enables mathematical transformation—ciphertext encrypted for $PK_A$ converts to ciphertext decryptable by $PK_{User}$, but the transformer cannot access plaintext.

- Distribute credentials: Owner sends VC and $RK_{A \to DID}$ to the platform (VC may go directly to user; $RK_{A \to DID}$ goes only to platform).

Phase 3: Proxy Access

This phase returns data control to the end user. Only after permission verification and successful key delivery does data become readable locally. Data visibility remains consistent with permission state—not determined by the platform.

- Request access: User presents VC to platform, requesting $v_N$’s key.

- Platform verification: Platform verifies VC signature validity, expiration, and DID matching.

- Execute re-encryption:

- Platform uses $RK_{A \to DID}$ to compute on $C_A$.

- Result: $C_{DID} = ReEnc(RK_{A \to DID}, C_A)$.

- Key point: Platform obtains $C_{DID}$, but lacks $SK_{User}$, so it cannot recover $K_N$.

- User decryption:

- User downloads $C_{DID}$.

- Decrypts locally: $K_N = Dec(SK_{User}, C_{DID})$.

- Uses $K_N$ to decrypt original data.

This design achieves encrypt once, authorize many. The Owner avoids re-encrypting GB-scale files for every new user—only a small re-encryption key is generated. If a user loses their local key but authorization remains valid, they can re-obtain it without re-engaging the Owner’s publishing workflow. This keeps user complexity and engineering costs within a practical, scalable range without sacrificing security boundaries.

Permission Revocation and Forward Secrecy

In decentralized systems, we must accept a security assumption:

Once data is decrypted and leaked during legitimate authorization, technical means cannot recover leaked copies.

Therefore, revocation aims not to erase the past, but to block future unauthorized access.

This scheme implements three-level revocation:

Level 1: Platform Layer — Immediate Block

- Operation: Owner instructs platform to delete stored $RK_{A \to DID}$.

- Effect: Platform loses ciphertext transformation capability. User holds $C_A$ but cannot convert it to a decryptable format.

- Characteristics: Fastest response, but relies on platform execution.

Level 2: Verification Layer — Logical Invalidation

- Operation: Owner uses VC Revocation List or expiration mechanisms.

- Effect: Platform checks on-chain state before re-encryption; if VC is invalid, service is refused.

- Characteristics: Switch-like control without physical key deletion; publicly auditable.

Level 3: Version Layer — Forward Secrecy (Key Rotation)

- Operation: Owner generates new version $v_{N+1}$ with fresh random key $K_{N+1}$.

- Effect: Old authorizations (for $v_N$) naturally fail for new versions. Revoked users cannot decrypt new data even with old keys.

Note: This mechanism is sometimes called “Future Secrecy” in cryptographic literature, as it protects future data from compromised past keys, similar to Signal’s ratchet mechanism.

System Availability When Platform Fails

Any serious data system must answer an inconvenient yet strictly realistic question:

What happens if the platform is gone?

“Gone” includes active malice or shutdown, and passive failure: bankruptcy, regulatory shutdown, mass node failure, or operator disappearance.

If the system collapses in such cases, it remains a hidden centralized system regardless of its daily elegance.

We analyze several extreme but realistic scenarios.

Scenario 1: Platform Unavailable, but On-Chain & Off-Chain Storage Exist

The most common and mildest failure.

State Assumptions

- Platform API inaccessible

- Blockchain network normal

- IPFS/Object Storage encrypted data accessible

- User and Owner retain their key materials

Impact on Knowledge Contributor (Owner)

- No data loss: Data resides in decentralized or independent storage, unrelated to platform lifecycle.

- Sovereignty intact:

- Symmetric key $K_N$ remains local

- Ciphertext $C_A$ can be decrypted by Owner

- New version $v_{N+1}$ publishing requires no original platform

- Only loss: Automated authorization execution temporarily interrupted. Platform no longer performs PRE computation.

Note: This does not invalidate authorization—only makes delivery paths more cumbersome.

Impact on Data Consumer (User)

- Already-obtained decrypted data unaffected

- Data where keys were not yet obtained:

- Cannot obtain re-encryption results via original platform automatically

- But VC remains valid and third-party verifiable

Permission facts still exist; only the default executor is missing.

Scenario 2: Platform Disappears, but Owner & User Want to Complete Authorization

A more challenging scenario with recoverable paths:

- User presents VC to Owner

- VC is platform-independent

- Verifiable via on-chain state or signature

- Owner re-executes key delivery locally

- Method A: Owner encrypts $K_N$ directly with User’s public key. Cost: one asymmetric encryption; data file needs no re-encryption.

- Method B: Owner redeploys PRE execution logic on a new proxy node.

- Key delivery completes; data decrypted.

Less smooth than platform automation, but the key point: the system is not locked. The platform is a default proxy, not the only channel.

Scenario 3: Platform Acts Maliciously or Selectively

This question must be answered directly.

Defense Point 1: Platform cannot forge permissions

- VC is signed by Owner

- Platform cannot forge or modify VC content

- Service refusal ≠ permission non-existence

Defense Point 2: Permissions and lineage are portable

- Lineage relationships are on-chain

- VCs can be verified by any new platform or independent node

- Owner can reissue $RK_{A \to User}$ to a new proxy node

The worst the platform can do is deny service, not tamper with facts.

Scenario 4: Platform and Partial Off-Chain Storage Fail Simultaneously

More extreme but not unimaginable. The design’s fallback logic:

- Chain stores only how to find data, not the only entry point

dataUriis replaceable and updatable- Owner can:

- Re-upload data to a new storage network

- Publish new version pointing to new

dataUri - Old version lineage remains verifiable; new version inherits naturally

Recovery cost is operational complexity, not irrecoverability.

Conclusion

Through this analysis, a key conclusion emerges:

Platform failure reduces automation, not data or sovereignty.

When platform exists: authorization is automated, experience approaches centralized systems. When platform is absent: operations are more cumbersome, but data, keys, and permissions remain complete and recoverable.

In this architecture, the platform is not a data custodian, not a permission arbiter, not a key holder—just a replaceable, bypassable computation and verification proxy. When it exists, the system works well. When it disappears, the system remains salvageable.

Auditability

When discussing decentralized data systems, a frequently avoided but essential question is:

Since we cannot technically prevent users from downloading and copying data, why does auditability matter?

If auditability means preventing all violations, it will fail. But if the goal shifts to maximizing traceability and responsibility certainty under inevitable risk, auditability becomes concrete and valuable.

Let’s clarify through a realistic scenario.

Suppose:

- Data version $v_N$ appears in an unauthorized channel

- Data has been decrypted and spread; technical recovery is impossible

- Three questions must be answered:

- Does this data really originate from our system?

- Who was the last legitimate accessor?

- Is there an evidence chain for legal action?

Step 1: Confirm Data Identity

- Chain records

ContributionFingerprintfor $v_N$ - Leaked data’s hash fingerprint can be recalculated

- If both match, this confirms the same logical version

This step avoids platform subjective judgment—any third party can reproduce this verification.

Step 2: Trace Complete Access Path

Once version is confirmed, we can answer: who, when, was legally authorized to access $v_N$?

Evidence sources:

- On-chain lineage records: $v_N$ publish time, operator DID, lineage version relationships

- VC authorization records: which DIDs held $v_N$ access permissions

- Platform audit logs: which VCs triggered re-encryption requests and when

If these records were generated normally during authorization, they serve as cross-verification sources.

Step 3: Narrow Responsibility Scope

Auditability does not guarantee identifying the unique leaker. But it can shrink an infinite responsibility space into a manageable, investigable, litigable scope.

Example:

- When $v_N$ leaked after a certain timestamp

- Within that window:

- Only 3 DIDs held valid VCs

- 2 never triggered re-encryption

- Only 1 DID completed key acquisition before the leak

The system has done its part: compressing technical uncertainty into a range where law can intervene.

Step 4: Provide Evidence for Legal & Compliance

This is where auditability lands. In the real world, rights protection depends not just on technical correctness, but on:

- Reproducible behavior

- Immutable evidence

- Clear authorization relationships

- Attributable responsibility

In this architecture:

- VC is an explicit authorization declaration

- On-chain lineage is an immutable timestamp anchor

- Key delivery behavior proves permission activation

System output is not just logs—it’s an evidence package ready for legal and compliance processes.

Summary and Outlook

One more emphasis: Any data system that allows human reading cannot technically promise zero leakage. This scheme never aimed for that. We cannot stop users from downloading data, but we can trace back to the last legitimate accessor.

This DID + PRE data lineage permission scheme essentially seeks balance between performance, security, and decentralization.

- vs. Traditional ACL: Returns permission control to users. Data leaves the warehouse, but permissions travel with it.

- vs. Fully Homomorphic Encryption: More engineering-feasible, with minimal latency. Introduces a semi-trusted proxy node (platform) to share computation load while cryptographically ensuring the proxy cannot misbehave.

This architecture provides a practical engineering paradigm for compliant data element circulation in the Web3 era. For extremely high-confidentiality scenarios (e.g., preventing platform side-channel attacks), introducing TEE (Trusted Execution Environment) as a stronger trust anchor may be necessary—a topic for future discussion.